The Illusions of Borders

How can exploring historical borderlands help students understand the complexity of political and cultural boundaries today? We often assume that the political lines on modern maps are fixed and represent clear breaks between nations. In reality, these lines are rarely so simple. Cross-border connections—like those between the Southwest United States and Mexico, disputes in the Himalayas, or the unclaimed Bir Tawil—show that borders are dynamic and often contested. By examining historical examples, we can help students see how political and cultural boundaries are shaped, negotiated, and experienced over time. Let’s explore one of history’s most illustrative cases.

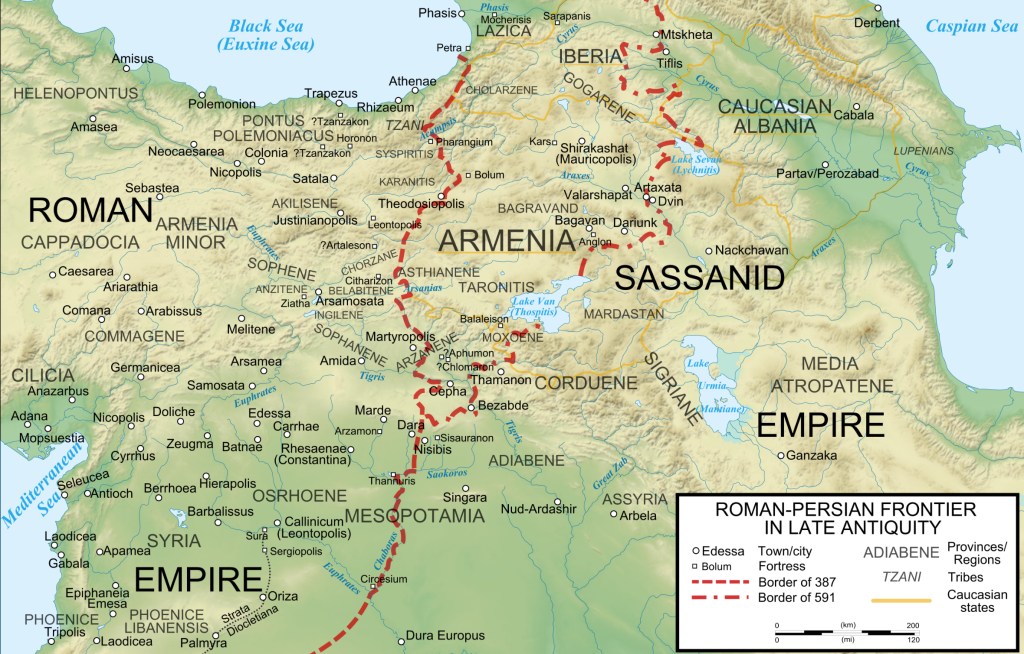

When we think of ancient empires, it’s easy to imagine vast, uniform territories ruled from a distant capital. But along the edges, especially where Rome and Persia met, the story was much more complicated. The Roman–Persian frontier, stretching roughly from the Euphrates in Mesopotamia up through Armenia and the Caucasus, was not just a line on a map. It was a dynamic crossroads, where multiple civilizations met, mingled, and influenced each other for centuries.

On one side stood the Roman Empire, bringing Greco-Roman architecture, language, and administration. On the other, the Sasanian Persians, whose art, governance, and Zoroastrian religion shaped the region. Between these giants lay a frontier that was never stable. Cities, fortresses, and trade hubs changed hands repeatedly, creating opportunities for cultural blending rather than purely military conflict.

A Melting Pot of Cultures

Because of its location, the frontier absorbed influences from Greco-Roman, Persian, Armenian, and Arab cultures. The merchants and soldiers that frequented the area brought new artistic styles, religious practices, and administrative systems. A visit to a market could offer Persian silks, Greek pottery, Armenian wine, and Arab spices. A house might have Persian-style courtyards, Greco-Roman mosaics, and locally carved inscriptions. Multiple beliefs and rituals from Zoroastrian, Christian, and local traditions coexisted. Written texts might include Latin, Greek, Aramaic, and Persian texts in the same document.

Visualizing the Frontier

The borderlands became a laboratory of cultural exchange, where the identities of local populations were constantly reshaped. It’s not hard to picture the same types of interactions in today’s world. The hundreds of US military bases spread throughout the world bring American soldiers into contact with numerous cultures. Exchange student programs transport students around the world. Movies can be seen on opening day in a theater or watched on a screen in the middle of nowhere. As social studies teachers, we have the opportunity to use the world around us to highlight the same processes unfolding today. Do borders matter? Of course, but not always in the ways we expect them to.

Recommended Resources

The Byzantine Empire and Persia

Ryan Wagoner

The Lyceum of History

“I am indebted to my father for living, but to my teacher for living well.” — Alexander the Great

Follow me on: Blog | TpT | YouTube | X | Instagram | Facebook

Leave a comment