Introduction

What can a city lost to the desert for centuries teach students about trade, culture, and human ingenuity? In 1812, Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, guided by a Bedouin, rediscovered Petra, a city hidden in the canyons of what is now Jordan. He found the ruins of a once-thriving trade center that connected the riches of Arabia to the wider world. While locals had long known of Petra, Burckhardt’s visit reintroduced it to modern audiences. This remarkable city—carved directly into the rocks, situated in a harsh desert, yet capable of hosting royal entourages at its height—offers students a vivid example of human creativity, adaptation, and the enduring impact of trade networks.

Origins and Rise

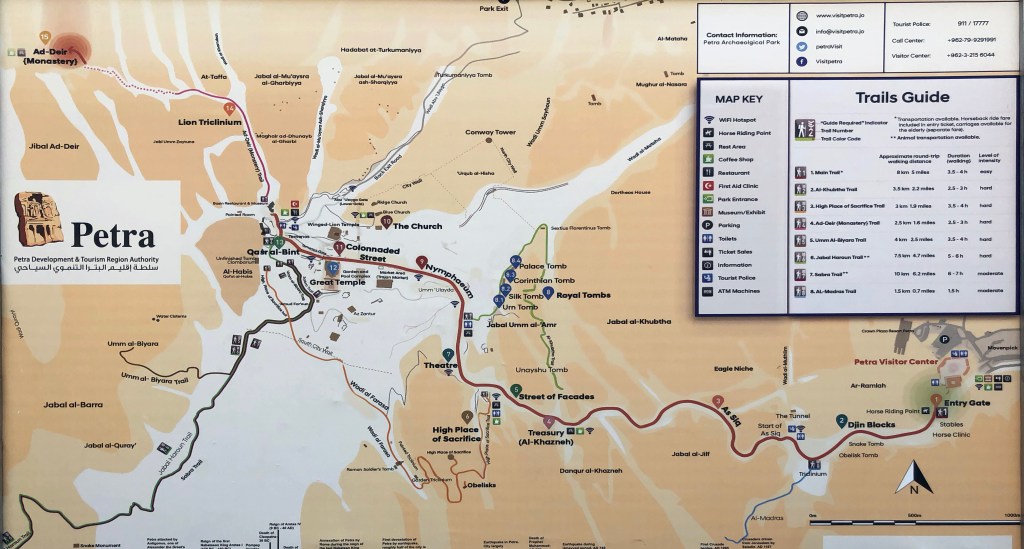

The Nabataeans, an Arabian tribe who migrated to the area where Petra, their capital, is situated around the 6th century BCE. They quickly established themselves as a center of commerce. By mastering desert engineering, including complex irrigation and water distribution systems, flash flooding safeguards, and a city that once held as many as 20,000 to 30,000 residents, they left their mark on the area.

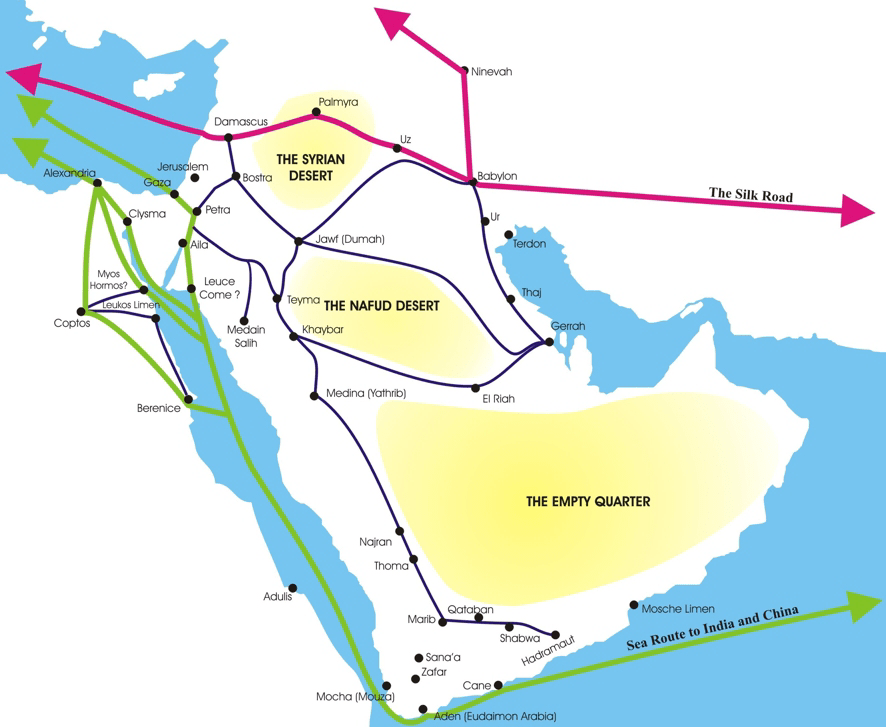

They first appear in the written records in the 4th century BCE by Greek historian, Hieronymous. Unlike other nomadic peoples, they did not immediately settle or centralize early. Instead, they developed a hybrid economy: part caravan trader, part desert mediator, part oasis manager. By the 2nd century BCE, they controlled large portions of the incense trade route connecting South Arabia with the Levant and to the wider Mediterranean world and beyond.

High Point and Decline

In 106 CE, Roman Emperor Trajan formally annexed the Nabataean, naming the new province Arabia Petraea. Rather than resist, Nabataean elites integrated. Realizing the futility of resistance, they took the opportunity to allow a super power to take command of their defense and further secure their trade routes.

This relationship held sway for a couple centuries before a series of factors would lead to Petra’s fall from power. Over time, Red Sea maritime routes replaced land caravans. Rome prioritized ports like Berenike and Alexandria and the Sassanid wars disrupted desert corridors. A major earthquake in 363 devastated Petra’s water system and by the time of the Islamic conquest in the 7th century, the city had fallen to the status of a small village, known only to the locals.

You see, their wealth never came from conquest, but through taxation, convoy protection, and water rights. They recognized the power of trade diplomacy and the power it gave them. They understood geopolitical leverage. Can we not tie modern trade wars, with all of the opinions that come with them, into our lessons as social studies teachers?

Enduring Significance

The Nabataeans are a reminder that trade is not passive exchange; it is geopolitical leverage. It is not just through military force that a civilization expands. One just has to look at how societies use tariffs and economic sanctions to flex their power. It also reminds us of the wonders and dangers of humanity taming inhospitable lands (think of Las Vegas, NV). What better way to tie in the ancient past with the very problems faced in our modern world? As with any complex situation, there are no clear black and white answers. There weren’t then; there aren’t now. But if we can get students evaluating options, we’re on the right track.

Recommended Resources

Ryan Wagoner

The Lyceum of History

“I am indebted to my father for living, but to my teacher for living well.” — Alexander the Great

Follow me on: Blog | TpT | YouTube | X | Instagram | Facebook

Leave a comment